The Mafia has been part of Sicilian life for generations, and so has the battle by police to arrest its leaders. The elite unit that goes after them is called the Catturandi, which means “the catchers” – one of its officers told Max Paradiso about the shadowy world in which he works, and how he kept his job hidden from his girlfriend until she recognised his bottom on TV.

The only time you are likely to see a member of the Catturandi is when they arrest a mafioso. They are the men “without a name and without a face” – when they carry out operations they wear balaclavas to ensure they can’t be identified.

“We prefer to be called ‘The Band of Lions’ because that’s what we are: wild, free, and ready to attack at any given time in this jungle,” says IMD.

There are fewer than 20 of them, and there is an obvious reason why the keep a low profile.

“Back in the day, you would receive death threats from the bad guys, goat heads sent directly to your house – it wasn’t pleasant,” he says.

In the 90s he also received photographs of his car number plate, marked with a red cross. The threats drove some of his colleagues to leave the Catturandi but not IMD – and over the years the risk of assassination has reduced.

He and his fellow officers find they often develop strangely intimate relationships with the criminals they track. They can wiretap and tail them for decades before making an arrest.

“It’s like living with these people. You hear them conceiving their children, you listen to their family issues, you see their kids growing up and their emotions become yours,” says IMD.

One of the men they bugged was a doctor in Palermo, who is now in jail.

“He was really knowledgeable, we all learned Italian literature by constantly listening to him. We would take notes, get books he mentioned in his never-ending lectures to his kids. It was like listening to a radio programme and we were all fascinated by his manners, his way of thinking and his creativity. It was hard to believe he was a mobster.”

The weeks after an arrest can be unsettling.

“You don’t see them any more – it’s psychologically hard to cope with and, as they were part of your daily life, you start missing them,” says IMD.

In his two decades with the police, IMD has helped to arrest nearly 300 mafiosi, including Giovanni Brusca, notorious for kidnapping and torturing the 11-year-old son of another mafioso who had betrayed him. Brusca had the boy killed and the body dissolved in acid – as a result, the child’s family couldn’t bury him.

At the moment of arrest, when the Catturandi storm a mobster’s house, IMD says he can have mixed feelings. “You want to ask them a lot of questions: Why do you kill? Why do you do that to another human being?”

But the opportunities for conversation are limited, and any exchanges tend to be unsatisfying.

“When we got Brusca, ‘The Pig’, he started weeping like a child. Provenzano, the boss of bosses, on the other hand, remained silent and whispered to me, ‘You don’t know what you’re doing.’ But we got them, and that’s what matters.”

Brusca was a key player in the crime that inspired IMD to join the police. On 23 May 1992, the Mafia placed half a tonne of explosives under the road to Palermo’s international airport, killing the leading anti-Mafia judge, Giovanni Falcone. Brusca was later identified as the man who pressed the button setting off the bombs.

“I was at my girlfriend’s 18th birthday party,” says IMD, who was a biology student at the time. “Her father was the head of the Palermo police response team and when the bomb blasted, the pagers of all the police officers at the party went off at the same time and everybody left in tears. That was this girl’s debut into society.”

IMD immediately wanted to find out what was going on but when he realised the road to the airport was sealed off, he decided to drive his motorcycle to the centre of Palermo instead to see how people were reacting.

“Right there,” IMD recalls, pointing at a little piazza, “I saw a bunch of guys laughing and cheering while eating their panini. I went up to them and I told them Judge Falcone got killed. They stared back at me and said, ‘What the hell do we care?’

“I knew what I wanted to do. The following day I joined the police force to catch as many bad guys as I could.”

At that time, few young Sicilians wanted to join the Catturandi – partly because the job was too dangerous – so IMD’s application was accepted readily.

“Most people you knew would stop talking to you or they would spit in your face because being a cop was considered an unspeakable betrayal,” he says.

He dropped his studies and while his old university friends were “chasing girls in nightclubs”, as he puts it, IMD was tailing Giovanni Brusca and other Mafia bosses such as Salvatore “Toto” Riina, who ordered the Falcone murder.

While following Brusca, IMD and one of his colleagues ended up in Cinisi, a small town near Palermo.

“There was this group of girls so we approached them. The idea was to get introduced to people in Cinisi without raising suspicions. Of course it worked out… we got the fugitive but I had to marry her afterwards,” he laughs.

Their dates were unusual. His girlfriend – unaware of what was going on – provided useful cover.

“Instead of taking my girlfriend, now my wife, to nice beaches to kiss under the stars, I would take her to horrible places, dead-end roads paved with garbage, just because I was following the fugitive’s lover. We would start embracing and she would ask: ‘Why here of all places?’

“After dropping her off at her house, I would go back to the office and report.”

He used to tell his loved ones that he worked at the passport office. But when he and his fellow Catturandi caught Brusca, “everybody was in front of their TV screens, videotaping the arrest”, he says.

“When my wife [then girlfriend] saw those men wearing the balaclavas she noticed a familiar rear end and she called me. I couldn’t hide the truth any more. I told her, ‘Please don’t say anything to Grandma otherwise the whole world will know.’ Luckily, she was able to keep the secret.”

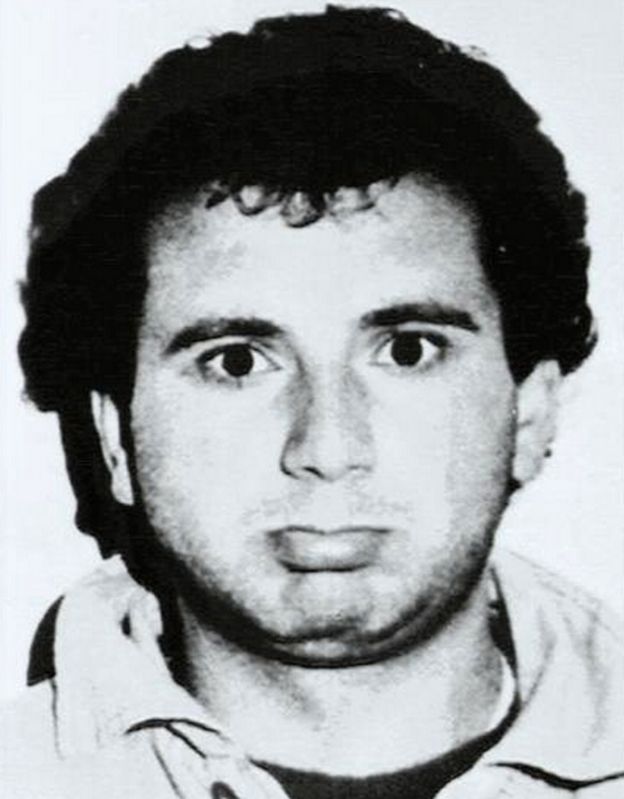

Italy’s most wanted mafioso today is Matteo Messina Denaro, also known as Diabolik – a nickname he took from an uncatchable thief in a comic book. The head of the Sicilian Mafia, he has been in hiding since 1993 – police believe he is living abroad, possibly in South America.

He once boasted that he could “fill a cemetery” with his victims, and last year it emerged that he had been communicating with fellow criminals using a code that referred to sheep. Messages between them included “The sheep need shearing” and “The shears need sharpening”. Eleven men were arrested in Sicily – IMD was there – but Denaro himself is as elusive as ever.

While the Sicilian Mafia is not as powerful as it was 20 years ago, it is still a problem for the island.

“They know they can’t kill people as they used to, so now the whole system has evolved into an intricate web of interests that entangles politics, finance and the very structure of Sicilian society,” says IMD.

For some, especially teenagers and tourists, the Mafia still holds a romantic aura. On Palermo’s street corners stallholders loudly advertise Godfather T-shirts, gun-shaped cigarette lighters and statuettes of men with moustaches and shotguns with one hand placed over their mouths. Muto sugno, Mum’s the word, it reads on the base of the miniatures.

One of these stalls stands just a block away from Via D’Amelio, a dead-end residential road where, on 19 July 1992, a Mafia bomb killed another judge, Paolo Borsellino. He was known as the “the good man of Palermo” for his stand against organised crime.

“These street stands are a paradox, just like this town,” says IMD. “We would like to be as civilised as the rest of the world, but we never let go this perverse fascination with the criminal underworld.”